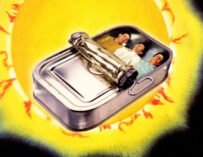

How the electro-pop classic, with one of the catchiest synth melodies, was inspired by the dropping of the atomic bomb

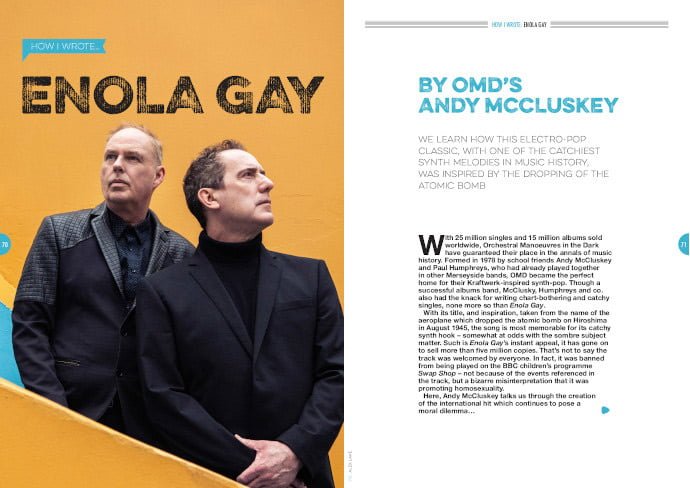

With 25 million singles and 15 million albums sold worldwide, Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark (OMD) have guaranteed their place in the annals of music history. Formed in 1978 by school friends Andy McCluskey and Paul Humphreys, who had already played together in other Merseyside bands, OMD became the perfect home for their Kraftwerk-inspired synth-pop. Though a successful albums band, McClusky, Humphreys and co. also had the knack for writing chart-bothering and catchy singles, none more so than Enola Gay.

With its title, and inspiration, taken from the name of the aeroplane which dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima in August 1945, the song is most memorable for its catchy synth hook – somewhat at odds with the sombre subject matter. Such is Enola Gay’s instant appeal, it has gone on to sell more than five million copies. That’s not to say the track was welcomed by everyone. In fact, it was banned from being played on the BBC children’s programme Swap Shop – not because of the events referenced in the track, but a bizarre misinterpretation that it was promoting homosexuality.

Here, Andy McCluskey talks us through the creation of the international hit which continues to pose a moral dilemma…

Released: 26 September 1980

Artist: Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark

Label: Dindisc

Songwriter: Andy McCluskey

Producers: OMD, Mike Howlett

UK chart position: 8

US chart position: –

“If you’re interested in Second World War aeroplanes then ultimately you have to come to the one that effectively ended the war, the B-29 Superfortress the Enola Gay that dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima. So I had decided in 1979 that I wanted to write a song about that.

“I never start with the lyrics but I will do some research, which goes back to being geeky. Before the days of the internet, you had to go and get books out of the library. As if I was doing a research paper or dissertation, I would read books, make notes, make lists of interesting facts, words and comments and just collect background information. I still have a ring binder which has my notes on the Enola Gay and I can see that I used some of those notes to help with the lyrics.

“The music always has to come first with Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark. It was written at Paul’s house because we used to work in the back room. His mother used to work six days a week and that was the place where we had space. Paul’s father had sadly passed away when he was young and his brother had gone to university so we had the free run of the Humphreys house. But I wrote this song on my own because Paul, in order to continue to receive his dole money, was forced into doing some labouring work in the rebuilding of the local baths in Hoylake. The thought of Paul Humphreys having to carry hod around is still hilarious!

“So, Paul was out and I was at his house and I just started writing the chords on the organ and the melody. Once I got those primary ingredients I then had the blueprint to write the song. It’s a typical linear OMD song, it is the same four chords all the way through and it never varies. The verse, the melody, the middle eight, it’s all the same.

“We worked it up as a band and played it in February/March 1980 when we were touring with our first album, before it was even released. There’s a recorded version of it that is on a compilation album before it was officially released. The famous drum machine sound wasn’t on the original version. We purchased a Roland CR-78 CompuRhythm, which was one of the first programmable drum machines. As well as having the presets like bossa nova and tango, you could actually programme your own drum sounds. So we programmed up that drum pattern and that became the bed for the whole track that we put on to it and is one of the most distinctive parts of the song.

“We recorded it when we went to Ridge Farm Studio to do our second album, Organisation. By that stage, I had finessed the lyrics. Obviously there are two competing arguments. One is that it was a horrific thing to do, to drop an atom bomb that killed up to 250,000 people. The counterargument is that it ended the war and saved millions of Japanese and American lives. I know that Paul Tibbets, the pilot, was absolutely sure that he helped end the war and save lots of lives by killing so many people with one bomb. So it was really an exploration of the moral dilemma and my ambivalence to the morality of doing such a thing.

“I chose to sing about the plane rather than the bombing itself. I was very proud of myself for writing the line, ‘Is mother proud of little boy today,’ because it had multiple meanings. The Enola Gay was Paul Tibbets’ mother’s name. That was a fairly bizarre thing, to name a plane after your mother and then go and drop an atom bomb. Plus, the bomb was codenamed ‘Little Boy’. When people said, ‘How can you write a cheerful-sounding pop song about such an atrocity?’ one of the defences I used was, ‘Is it worse than naming the plane after your mother and dropping the atom bomb?’

“The record company had accepted it, it had gone to the pressing plant, there were white labels and it was ready to go but I decided that I didn’t like the mix or the way I’d sung it. I insisted on going back to Advision Studios in London to recut the vocal and remix it. That second version is the one that became the single and ended up selling five million copies, mostly in Europe. It was even used for the opening ceremony of the 2012 Olympics.

“Melodically, it is very strong. One of the other elements is that, for people for whom English is not their first language, it’s one of those early OMD songs where there is no sung chorus. The synth melody is the chorus, so even if you can’t speak English you can sing along. It’s international, you don’t need to know the words because there are no words. I also think there were a certain element of geeky young men and girls who also found appeal in its intellectual content.

“I am proud of writing it and I do genuinely think it was a great piece of work. I was very young when I wrote it. I think it shows a distillation of the songwriting craft that Paul and I had both been developing together since we were 16. But there have been times when I’ve asked myself how appropriate it is to feel proud about writing about such an atrocious incident.

“I do sometimes catch myself on stage playing the song, with the audience going crazy and jumping up and down, clapping and shouting, and it does cross my mind that there’s something rather strange about the fact that we’re closing a euphoric set with a song about something so appalling. So there remains an ambivalence about it, which is also part of its strength. It has a depth and a darkness and a requirement to ask yourself moral questions.”

![Songwriting Credits… best new music playlist [September 2023]](https://www.songwritingmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/songwriting-credits-september-2023-335x256.jpg)

Related Articles